PARIS — HIV may be dismissed by some as a treatable disease, but as middle-aged Frenchman Jean-Luc Romero can attest, living with antiretroviral drugs means a daily battle with queasiness.

Side effects are an often-overlooked downside of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), the drugs that have turned HIV from a death sentence to a manageable illness.

If the media chirpily dub HAART a drug "cocktail", HAART is definitely not a fun experience, Romero said.

The powerful drugs can have toxic side effects and, unless a cure for AIDS is found some day, have to be taken for the rest of one's life.

"They are like tiny bombs which prevent the AIDS virus from replicating, but also they destroy a host of other things," the 51-year-old councillor for the Paris region said an interview.

In his long litany of woes, Romero suffers from aching muscles, acute diarrhoea and lipodystrophy, a notorious HAART-related condition in which fat can accumulate on the belly or as a "buffalo hump" on the back of the neck, yet disappear from the face, leaving a patient looking sunken-eyed.

He is haunted especially by exhaustion, a never-ending feeling of being unwell and of "premature ageing", that his body and a mind have become old before their time.

"I don't know what it's like to sleep for more than three hours in one go," said Romero. "Even when I come back from holiday, I can't say, 'I feel really relaxed.'"

Life for Romero is dictated by the pill box. He takes six HAART tablets a day, four tablets for diabetes -- another HAART risk -- and throughout the day takes quantities of medication for the diarrhoea.

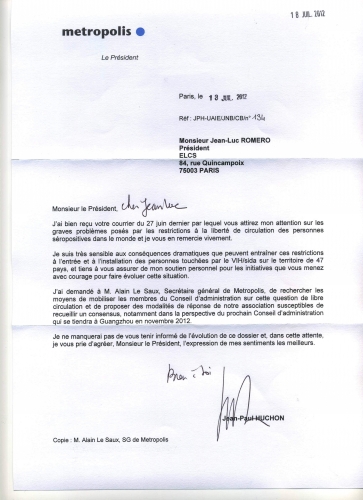

Even so, Romero, as president of an association gathering local officials in the fight against AIDS, is the first to praise HAART as a lifesaver.

In 1987, at the age of 27, he learned that he had the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).

At that time, such news heralded a long, painful and inevitable descent towards death. The only medication was AZT, which had "horrifying" side effects and had to be taken every four hours.

"We lived from day to day. There was no point planning beyond that. We saw people dying all around us, and we would say, 'That will be us one day.' We didn't think about the future, because the present was all we had. I remember thinking, 'I won't live beyond 30'."

All that changed in 1996, when HAART became available -- in rich countries at least, for it would take another decade for the lifeline to be cast to poorer nations in Africa.

Today, millions of people are not only kept alive by HAART but able to hold down jobs, have a social life or a family.

The drug regimen, initially a punishing 27 pills a day, has been hugely simplified -- some take a single pill a day -- and some of its side effects, including lipodystrophy, are not as bad as before.

In the light of this success, experts at the six-day International AIDS Conference opening in Vienna on Sunday will debate whether treatment guidelines should be overhauled, so that HAART is given to patients when their infection is at a lower threshold. Reducing mortality will have to be balanced against side effects.

If HIV has been reduced in the public's mind to the status of a chronic illness, many people have still not placed it on the same footing as routine conditions such as cancer or heart disease, said Romero.

In France, shame, stigma and discrimination, especially in employment, are deeply rooted, he said.

"At the time when I found out I was infected, there was compassion. Today, the notion of blame is even stronger," said Romero.

Living with HIV "is something that you never get used to", he said.

"For nearly 25 years I have had to live in the consciousness of death, and that has forced me to squeeze every single drop out of life."